Authenticity

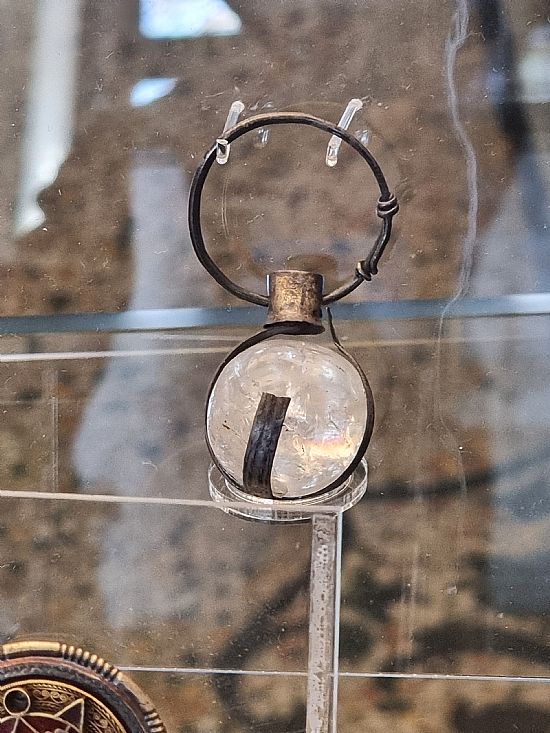

(Above : an authentic reproduction of the "King Alfreds Jewel" in the Shaftesbury Museum)

Authenticity is very important to any group that considers itself to be an historical reenactment society, as opposed to a LARP or Cosplay group where imagination can roam free and anything goes.

SÆXIA is committed to maintaining a high level of authenticity, however, as many reenactment societies find, maintaining 100% authenticity in all areas is quite a challenge, not least because there are different approaches to this important area taken by different reenactment groups.

The broad understanding of what "authentic" means is an item of equipment, weaponry or clothing that is a direct copy of an archeological find, and that anything else is simply "not authentic". Over the last few decades especially this has also come to include the manufacturing process of that item and the base materials used to fabricate that item, and the tools used to work those materials into the item.

Above is an authentic recreation of an Anglo Saxon Hall, at Butser Ancient Farm in Hampshire. This Hall, along with another immediately next to it, have been constructed to the exact dimensions of two Halls uncovered at an archeological site around a mile away, on a hill visible from the two reconstructions.

However, when excavating the original remains at the archeological dig in 1971 & 1972 there were of course no actual Halls existing as buildings. The archeologists were uncovering the "footprints" of these two structures; the foundations including post holes and trenches dug for where the upright posts were dug in and walling constructed, supporting the beams and trusses of the roof.

Butser's own website details further that this Hall, and the other next to it, are both reconstructed in slightly different ways, using techniques that were known to the Saxons of that period. This is because, as the Butser website explains in its article on the opening of this second Hall, there was no way of knowing what the original Halls actually did look like. The only approach then open to the team reconstructing the Halls at Butser was that of "Experimental Archeology" (EXARC)

(Above: the two reconstructed Anglo Saxon Halls at Butser Ancient Farm, Hampshire)

Experimental Archeologyis of great importance in Early Medieval Reenactment, as this time period of over 500 years has a far from complete archeological record of hard evidence for historians and reenactors alike to draw from.

(Above: work progresses on reconstructing a fragment of an Early Medieval Frankish belt buckle)

In cases where the hard physical evidence is fragmented, or missing entirely, it becomes almost impossible to claim total authenticity in recreations of the Early Medieval time period, and educated theorising along with EXARCapproaches become necessary. This kind of speculative approach, forming concepts based on available sources and hard archeology, can lead to "Interpretive Archeology" (INTARC) which, although closely following many of the principles of EXARC, remains a little more flexible in being able to "plug the gaps" in our knowledge. An additional term that is sometimes used to describe historical research undertaken by historical reenactors is Experiential Archeology, which covers a broad range of the kinds of activities reenactors have to learn and perform when attempting to recreate the past as an immersive experience both for themselves and for the public to be able to effectively "time travel" into!

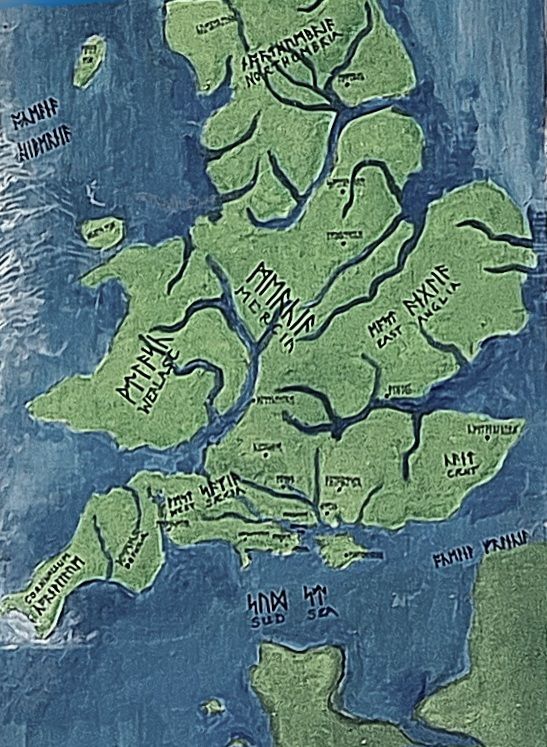

The map of part of Anglo-Saxon Britain was originally painted as a teaching aid for use at the Wareham Saxon Festival 2022. Graphically this map draws inspiration from two sources: a Roman period map of Europe, and a later medieval map of Britain made in the 13th century.

(Above: the Saxon England map on display at the Wareahm Saxon Festival 2022)

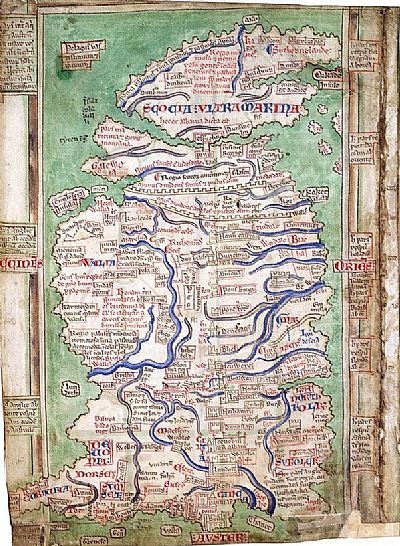

(Left: The Roman era map of Britain)

(Left: The Roman era map of Britain)

(Right: the 13th century map of the British Isles)

The 13th century map especially shows the significance of rivers as access routes inland. The Roman map is a little less detailed and yet from the various archeological finds along the Roman frontier with Germania we know that rivers were also used strategically in that period and that officials then would have had access to other maps which have unfortunately not survived to the present day.

The Saxon England map, then, takes influence from the custom of exaggerating the rivers and inlets from the sea on mapping from the ancient world and medieval period, a time before more advanced cartography was available. In addition the Saxon England map features place names in the Anglo Saxon "Futhorc" or runic alphabet, that was being developed by King Ælfred and his scribes into a phonetic alphabet as part of his educational reforms for the restoration of Wessex after the devastation of the Dane wars.

Lastly this teaching aid features a far more accurate outline of the British Isles than is accurate for the time period, however this again is simply to cater to the modern public recognition of what the map represents. Can this map be considered Interpretive Archeology? Not really, as from the outset the plan was to create a teaching aid for the 21st century mindset of public visiting SÆXIA events, and despite drawing influence from real sources and teaching on real occurrences it was not painted to resemble either of the pieces of hard evidence available.

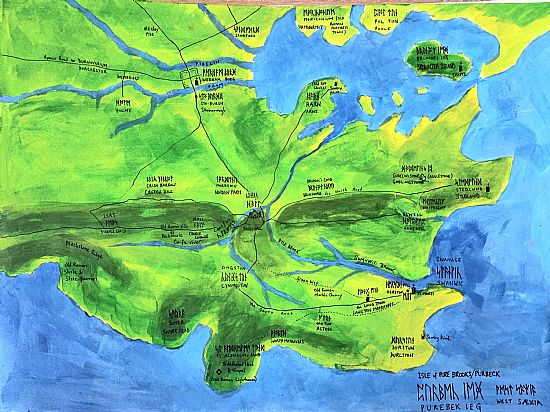

However, should such a teaching tool be taken seriously as an effective way to bring the past to life? Our feedback has been most definitely yes, as we have since used the map, and another of SÆXIA's immediate home territory of the Isle of Purbeck, as part of an effort to recreate a West Saxon military Fyrd recruitment field HQ, and as part of the kind of tactical administration that a Thegn or Ældorman under orders from King Ælfred might have at his disposal.

An area where SÆXIA at times takes a different approach to our historical recreations is the way we sometimes combine elements of earlier period kit and/or jewelry with later periods being reenacted. This is again for the purposes of education and raising more awareness of all things "Saxon" as the Early Medieval Reenactment community is still very much dominated by "Viking" reenactment, not to mention the plethora of "Viking" themed movies like "the Northman", "13th Warrior" and the Russian film "Viking", along with TV/Netflix/Amazon Prime series like "The Vikings" and "the Last Kingdom", which portrays Danes/Vikings consistently in a far better light than the Saxon characters! This is compounded by a common "reenactorism" often presented to the public, as in large events the majority of "Viking" reenactors are often simply split in two so that there might be a fairly balanced opposing "army" in the combat displays. When the public comment that the "Saxons look just the same as the Vikings", the response is usually something along the lines of, "well everyone kind of did look the same back then". This is something SÆXIA is working with other specific Anglo-Saxon reenactment groups to address, as there were in fact a number of key differences in how Early Medieval Scandinavians/"Vikings" and Anglo-Saxons looked and lived throughout the Early Middle Ages.

That said, there were of course other areas in which Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon fashions followed each other. Although popular modern culture tends to romanticise and focus on battles and wars for supremacy and conquest, there was far more to be gained universally in trade, and continued analysis of archeological finds from all over northern Europe and beyond are confirming a vast and lucrative series of trade routes that connected far more of Early Medieval Britain to exotic foreign goods than was ever thought possible, from garnet stones brought all the way from India, to early Saxon ivory once thought to have been from Walrus tusks and now confirmed to be from African Elephants!